by Jason Bell, illustrated by Zach Bell

“I’ll pay him back,” Jo told Margie over the phone. She had the

greasy package in the glove compartment. Empty at 10 am, the gas station

sold banana mooncakes. Jo ate a second, put down the pay phone, and

wobbled back to the car.

Jo signaled but in a wide looping swerve stayed on 270 headed away

north from Memphis. In her Saturn, her stomach bumped against the

steering wheel. The car leaned close into the highway. She kept the

radio low so the song sounded like a washed-out disco playing above a

swimming pool.

Two orange trees grew by her pool and dropped their fruit all summer,

until the bees came and bored their way through oily skins to the

flesh. Cheeks swollen with air and pain rising in her throat, Jo would

swivel to “Sunny” by Boney M. The water would be warm like an orange egg

yolk. At a precise but unknown temperature, pool water congeals and

enfolds limbs and little hairs in a lithe embrace. Weightless and

crystallized, the body floats suspended in space.

Carlos came and collected oranges for his grandmother. Her rheumatic

fingers begged for juice. While Jo swam laps, Carlos walked around the

pool, looking for the roundest specimens. He was a tall brown boy with

black hair around his shoulders and thick eyelashes. Over the summer, he

grew out his beard, first in patches along the cheekbones and then a

nice goatee, finally the moustache. Even after the oranges stopped, he

still came and watched Jo—she would pop her head above mid-lap and gasp,

“Hey Jose,” and he would smile big broad and gap-toothed and wave.

In August, the air turned cool early and withdrew into a corner,

tightening a lock of hoary hair around an index finger. Jo shivered as

the air caught her shoulders, and she left the pool and wrapped herself

in a six-foot long plush towel. A hand grabbed her long stomach and

pulled. She clenched her abdomen and gritted her teeth and grinned over

her shoulder.

She felt the baby kick and breathed through her nostrils, blowing a

strand of auburn hair out of her eyes. It would rot and the air would

buzz, intoxicated in the late morning, that uncomfortable hour between

breakfast and lunch, when the stomach begins to whimper but never fully

asserts its needs. The baby was hungry, but Jo ignored the promise of

fried whiting, fries, hushpuppies, and slaw. If she made time, she might

reach St. Louis before dinner. She could call Margie, in Memphis, and

explain why she was missing.

When Jo left for college and decided not to marry Carlos, her mother moved to Memphis.

“The house is too much. I can’t make it on my own.” She drank half

her cup of coffee. “In Memphis, I can see Richard as much as I want.

It’s more affordable.” Sipping her coffee. “It doesn’t matter whether

you visit me in Memphis or here” Bothering her bangs away. “Anyway

Richard would like to see you too I’m sure.”

Richard left Jo and her mom when she was 11 for no reason other than

he felt that LA wasn’t it and it was time. Plenty of time in Memphis.

After he left, the house was vacant. But Richard and her mother kept a

close correspondence. Marriage just didn’t work for them but it doesn’t

end up that way for everyone.

In Memphis, her mother bought a condo. Two bedrooms, a kitchen, a

living room, and a convertible dining space. Between the dining and the

living room, she pushed the TV, and would turn it depending on whether

her neighbor Margeline visited for coffee or whiskey and soda. Her

mother dyed her hair puce, painted her lips, rubbed her eyes blue, and

loved Family Feud. Every Thursday, she called Jo, said, “Margeline is

bringing over a slice of some supermarket strudel so I can’t talk long,”

and then talked until Margeline came in, screamed at her “Margie hold

up I’m talking on the phone” and let Margie wait outside the door

holding cherry strudel in her short overbronzed and wrinkled forearms.

“How’s Carlos?”

“You know I haven’t seen him for three weeks.”

“When’s he coming back?”

“I don’t know, if I knew you would be the first to know.”

“Where’d he go then?”

“I told you, he went to go look for office space with his partner in Vegas.”

“Office space? He runs one of those tattoo parlors.”

“He’s a tattoo artist.”

“How long does it take to find a strip mall to plop a tattoo parlor?”

Three weeks and four days, actually, and Carlos called her from the

lobby of a dentist’s office. They couldn’t find nothing, not for lack of

trying, because they had gone into literally every strip mall around

the strip and there wasn’t anything they could afford with the money

Carlos had borrowed from Richard.

Carlos went back to LA and kept doing tattoos out of other offices. A

dentist let him use his space after hours. Jo heard about abortions in

dentist offices, but never tattoos. As a coming home present, Carlos dug

out a marvelous canoe on Jo’s stomach: a sun smoking a spliff. Two

beads of sweat welled up on the sun’s forehead. Its mouth puckered

around Jo’s navel, and a line of smoke curled like lingerie towards her

breasts. Jo hated the feeling of the needle running over her belly, a

strange vibration that made her jaws hum, relaxed her thighs, and forced

her to float out of her spine, leaving a split open corpse in the

dentist’s chair. The needle sang like a drill. Jo was a vessel to sail

to the heavens. She was already pregnant.

The money never got back to Richard, and Carlos moved to St. Louis

when Jo was in her second trimester. He rented a chair at Iron Maiden

Tattoo in Overland. After work, he ate tongue tacos at a Mexican grocery

store. He took Jo’s calls when he had the time.

In Jo’s third trimester, her mother died in front of the TV eating a

bowl of Blue Bunny Ice Cream. Margie found the body and called Jo. Jo

flew into Memphis and was driving to see Margie when she decided to skip

the funeral. Margie would have given her a bed.

The offer to stay on the road is perpetual and tantalizing like an

orange about to rot in the grass—but rarely taken. Jo was a rare one who

moved to the next destination. St. Louis was five hours north. The

radio tickled her ear and she felt ready to come up and breathe.

The baby scratched at her stomach, running his fully formed nails

over her tissues. It tickled. Each teasing scrape worried Jo—she was

carrying a hairy beast inside her womb, a snouty pig with tusks and soft

cartilaginous hoofs. He cried for mushrooms, apples, chestnuts, and

blood sausage. Although Jo tried to feed him, he wanted to root around

her pelvis. Jo thought he might look like Richard, that Richard’s genes,

hidden inside her own flesh, might float to the surface and sculpt her

baby a button nose and pendulous lips.

Richard stopped at Margie’s after the wake. Flabby wrinkles dragged

his lips towards the earth. Once, he had clear aquamarine eyes. Boar

bristles sprouted from his puffy nose. He snuffled, and Margie hugged

him. Poking his head over hers, he looked with longing at the strudel

set on the kitchen table, mummified in clingwrap.

“Are you hungry?” Margie patted his flannel back.

“Please,” was all Richard said, and Margie was already plating a heavy

slice of strudel. Artificial red filling oozed from between slabs of

pastry. It tasted like margarine. The icing had dried. Richard ate the

strudel with his fingers, and licked them when he finished. His eyes

sought again the strudel, and Margie complied.

“Where was Jo?” He asked, suppressing a belch.

“She needed to go to St. Louis I guess, to see Carlos.”

Richard sat on the corduroy couch.

“That greaseball asshole owes me more than a little dough.”

Margie’s plastic lips tightened around her skull.

“Well he does!” Richard shrugged. “$10,000!”

Margie turned on the TV. Some quiz show.

“Jo told me to tell you she’ll pay you back.”

“She doesn’t have that kind of money.” Richard laughed and rubbed his front teeth with his finger.

When Jo hit St. Louis, she took a rest at Long John Silvers. Two

planks of golden fried fish later, she wobbled back to the car. The fat

on her face jumped. She bent over and took a greasy paper package out of

the glove compartment. There was a post office across the street, and

she crossed at the light. For the pay phone, she waited behind a woman

pushing a dog in a stroller. The receiver felt long and heavy in her

hands like a cudgel, or not even something real, a stone that could

become a sword or a playphone depending on the game. She called Richard.

“This is Richard Mendez, but I must have left the house for a bit. Leave a message and I’ll call you back.”

“Richard, it’s Jo. I have your money. Carlos gave it back. I just wanted

you to know that I had it, and I’ll pay you back. Margie should have

told you. But I can’t see you when I’m like this, and mom dead, so when I

have the baby and I’ll come back to Memphis and pay you back what’s

yours. That’s the least I can do.” And she hung up, her thin hair

sticking to her dry eyes. On the edge of St. Louis summer, oak pollen

brushed into every crevice. Yellow vegetable semen, trickling along the

wind. It laid in moist places and hatched into cankers and galls.

Hard knobbly skinned tumors pink on the inside. Outside the AC, the

pollen swirled into Jo’s eyes, and she rubbed and rubbed them until they

were red and she saw spots.

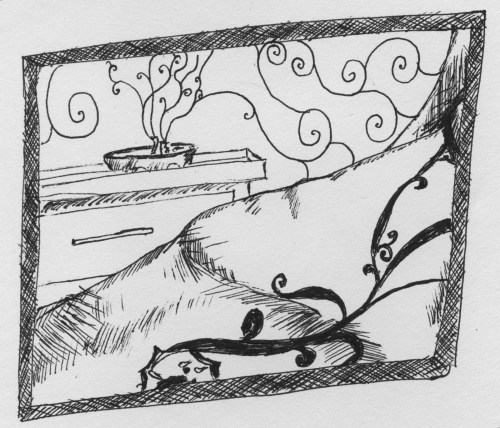

Iron Maiden Tattoo had a busted neon sign that read, “No pussies!”

and bars over the windows. Next door, a pho shop sold massages. The

smell of beef soup infiltrated the tattoo parlor. Carlos hated

Vietnamese food and would slur against the chinks while he etched

designs into backs and bellies. He was tattooing a train on a teenage

black thigh, head bent over his work, ignoring the pho in favor of sweet

incense.

“What’s the smell?” It was Andrew’s first tattoo, but the start of an

extensive collection. Unlike Jo, he adored the prickling heat of the

needle on his skin. For his entire life, however, he would hate

Vietnamese food and take great pains to avoid Iron Maiden Tattoo.

“It’s Barack.” Andrew craned his neck away from the flash on the

walls: a mermaid getting an enema, two dogs humping, and barbed wire

hearts. “What the fuck man,” Andrew said. A supremely unfunny joke? “No

really, it’s Barack Obama you’re smelling.” It smelled like burning

banana peels, sandalwood, hairy ass, spilled beer, and patchouli. And

the pho: cilantro and jalapeno, dishwater, and tripe and meatballs. “The

incense is called Barack Obama.” Andrew spit out a tight laugh.

“Barack smells like ass,” Andrew said.

“What, you don’t like this?” Carlos’s fingers traced the bloody train,

and he reached for a blue terrycloth to rub away the excess ink.

“I’d rather smell that soup.”

Before work, Carlos ate menudo at the grocery. Two telenovas played

simultaneously on two televisions. He slurped and ignored both

soundtracks. Besides Carlos and a chubby serving girl, the grocery was

empty. The girl brought Carlos a beer, and he gave her a small smile in

return. She thrust her chin out, an innocent, sweet repartee. The

telenovas burbled in the background. Carlos finished his soup and read a

newspaper. Then, he called his abuela from a pay phone outside the

grocery. She told him he was full of himself, and he laughed out of his

throat, slicked his hair back from his eyes, and hung up.

The door jingled. Andrew made eye contact with the fat woman walking

through the door. Dimpled wads of fat rolled off her elbows, and her

neck threatened to burst her straining collarbone. Thin hair fell off

her forehead in clumps. Her stomach was distended and poured over

ponderous legs, the ancient roots of redwoods pushing deeper and deeper

into the California soil for sustenance.

Carlos looked up from the tattoo and his face froze in a hello.

“I came for Richard’s money,” was all Jo said. Before Carlos moved

on, she reached into her pants and pulled out the greasy package. Again,

he stuttered. She unwrapped the butcher paper and paid him back.